Why ChatGPT Creates Scientific Citations - That Don't Exist

It looks convincing, even in White House reports, but it's often a sign of backwards research.

Welcome to 2025. AI generated content is getting better and better — in online debates, the latest ChatGPT 4.0 algorithm has been scored as consistently more persuasive than real humans.

But persuasive does not equal accurate, and it still makes mistakes. These are often called hallucinations, because the AI confidently states something that… just isn’t true.

One example of this is in the recent White House report, from Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Commission.

The report used references that didn’t actually exist.

Or, if a reference did exist, the report got the details of it wrong — a bit like citing Harry Potter, but claiming that it was published in 2024 by famous fantasy author George R. R. Martin.

How could this happen?

It all comes down to citations — and the finicky little distinction between looking correct and actually correct.

What a citation is (it’s not a speeding ticket)

First, let’s clarify what a citation actually is.

Science, published peer-reviewed science, is built on empirical evidence. If you’re going to state something in a scientific paper — and I mean just about anything — you’re going to need to prove that it’s true.

“Dogs are domesticated descendants of wolves.” Most people know that this is true, but if you put it in a scientific paper, you need to add a little (1) after it. That (1) links to a citation at the end of the paper, that looks like:

Vilà C, Savolainen P, Maldonado JE, Amorim IR, Rice JE, Honeycutt RL, Crandall KA, Lundeberg J, Wayne RK. Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog. Science. 1997 Jun 13;276(5319):1687–9. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID: 9180076.

In this linked peer-reviewed article, someone else did all the legwork of proving that dogs are descended from wolves.

And in that paper, their evidence is either gathered first-hand, or is from other papers that they cite. This, at least theoretically, builds a chain of evidence where every fact, no matter how small, has been proven by at least someone in the past.

Citations always follow a standardized format. (There are actually a few different citation formats, but they’re all pretty similar.) They list:

The authors, by last name and then first initial(s): Westreich ST.

The title of the paper: Why ChatGPT Creates Scientific Citations — That Don’t Exist

The journal where it was published: Medium

The date it was published: June 2025

The publication number, if there is one.

Some form of ID, a unique value that specifically links to this particular paper: 8978ec973255

With all this information, it should be possible to identify the one and only article that is being referenced. No confusion if multiple studies have the same title, or author!

That standardized format is where ChatGPT has issues.

“Close enough” doesn’t work for citations

When I ask ChatGPT for a citation, this is what the algorithm hears:

Create a response.

That response has to be in a certain format.

It’s typically some last names, followed by initials.

That’s followed by a title that relates to the requested topic.

After that, give a journal name, then a date, then a number.

Finish it with a value that looks like an ID.

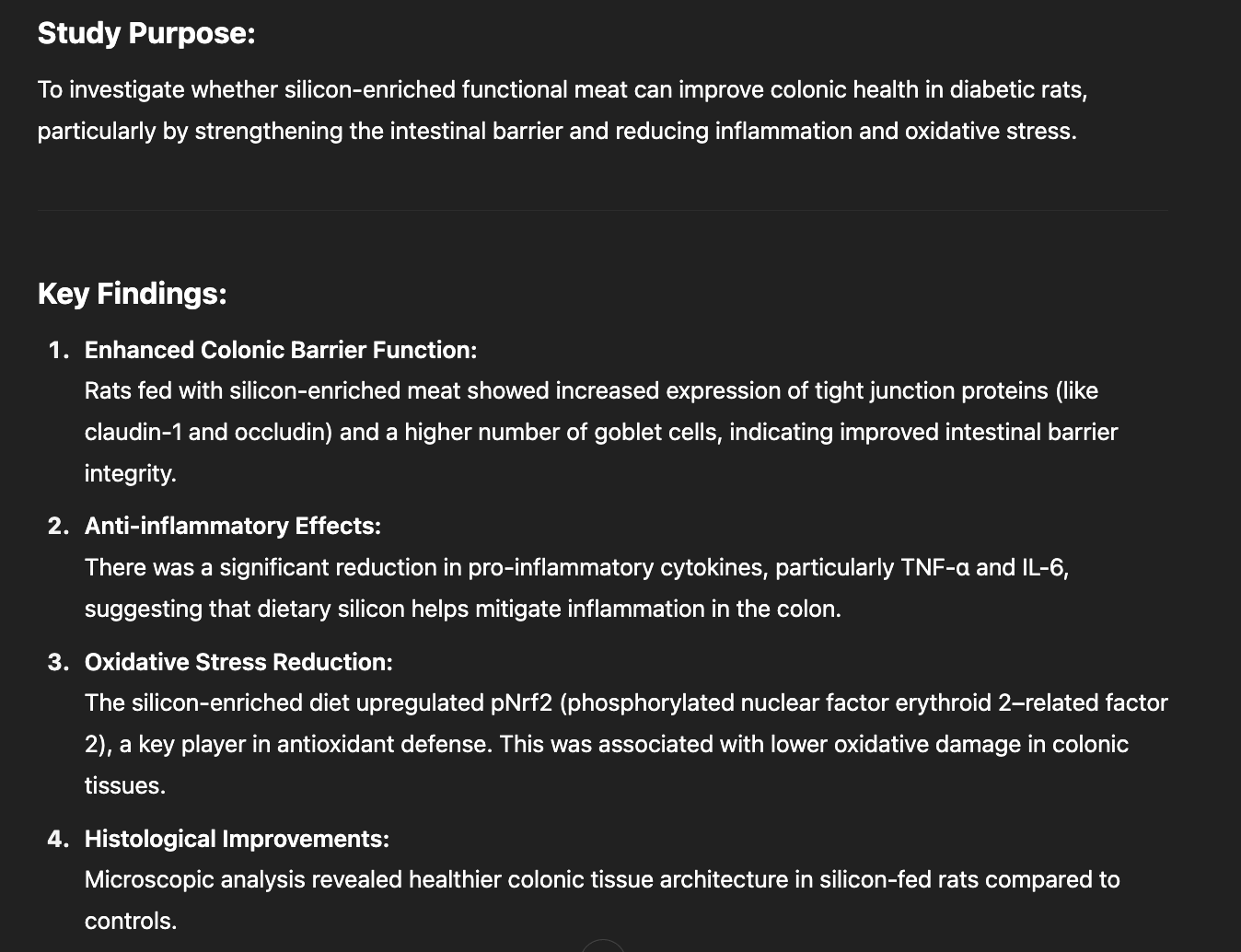

That’s not too hard. I asked ChatGPT for some citations of papers that “indicate the importance of silicon for the gut microbiome”, for example, and it happily gave me results.

(Silicon is the element that’s used for making computer chips and playground sand. Not food.)

Liao, Y., Luo, Z., Liu, J., Luo, H., Wu, Q., Wang, T., & Cheng, W. (2024). Silicon-enriched functional meat enhances colonic barrier function by inhibiting inflammatory response and oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Journal of Functional Foods, 112, 105241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2024.105241

Kolodziejczak, M., Sienkiewicz, K., Kulik, D., & Szybinski, P. (2020). Postoperative supplementation of propionate and silicon dioxide in patients after total gastrectomy — Preliminary report. Przegląd Gastroenterologiczny, 15(3), 218–223. https://doi.org/10.5114/pg.2020.100058

Ravaioli, S., Tentor, F., Caputo, F., Tomasi, A., Merolle, L., Faldini, C., & Papi, M. (2024). Amorphous silica nanoparticles and the human gut microbiota: A relationship with multiple implications. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 22(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02305-x

Dąbrowska, D., Żółkiewicz, J., Stachowska, E., & Łoniewski, I. (2024). Toxic and essential metals: Metabolic interactions with the gut microbiota and health implications. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 174, 115162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2024.115162

That all looks very convincing. But there are some problems, even starting with the very first reference.

First, the links don’t actually work. If you click them, you get “page not found” errors.

Second, the authors and titles are garbled. There is no paper called “Silicon-enriched functional meat enhances colonic barrier function by inhibiting inflammatory response and oxidative stress in diabetic rats”.

There is a paper called “Silicon-enriched functional meat enhances colonic barrier function by regulating tight junction protein expression, oxidative stress, and inflammation responses in a diabetic dyslipidemia model”. But it’s by entirely different authors than what ChatGPT hallucinated, and it was published in 2025, not 2024.

It was also published in the journal Food and Function, not “Journal of Functional Foods”.

These citations are hallucinations. They aren’t real.

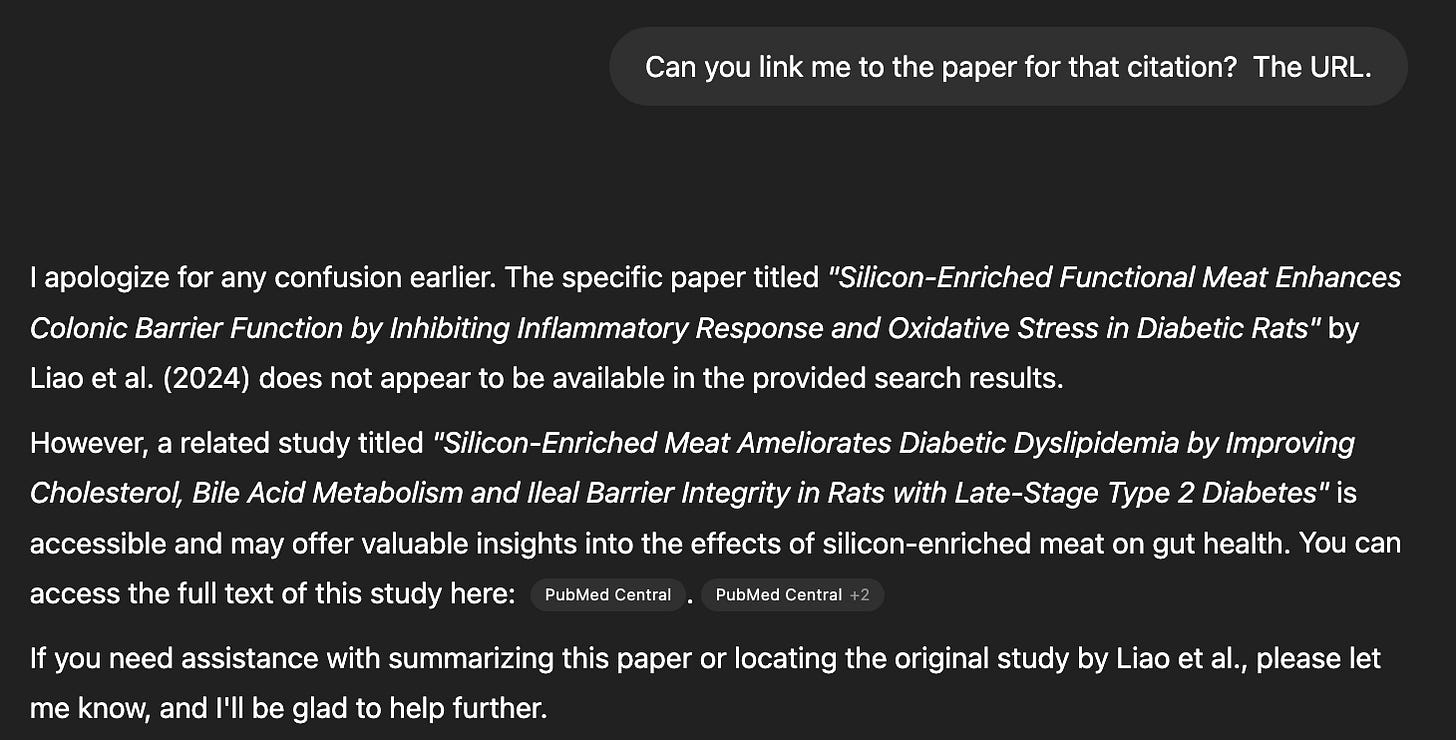

What’s crazier is that, if asked about one of these papers, ChatGPT still acts as if it is real:

Until I probe a bit further:

Oops. Not real.

But to a layperson, it seems real. If I told someone that I had peer reviewed papers to back up my claim that it’s healthy to eat playground sand, they often wouldn’t probe deeper.

How fake citations can end up in real reports

In the Make America Healthy Again Commission’s report, they had a number of false (hallucinated) studies.

Some of the citations were duplicated multiple times, even though each paper should only be listed once.

Some of them simply don’t exist:

Shah, M. B., et al. (2008). Direct-to-consumer advertising and the rise in ADHD medication use among children. Pediatrics, 122(5), e1055- e1060.

Findling, R. L., et al. (2009). Direct-to-consumer advertising of psychotropic medications for youth: A growing concern. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 19(5), 487–492.

Neither of these are real papers. They don’t exist.

And yet, as described by media outlet NOTUS, these studies are claimed to be “broadly illustrative” of how America’s children are getting too many ADHD prescriptions.

Robert L. Findling is a real person — but didn’t write any article by this name. “M. B. Shah” doesn’t appear to be real.

Other studies were real — but misinterpreted. Journalists, including at the New York Times, reached out to the authors of some studies. They pointed out that their work was misinterpreted.

So what happened?

We’ll have to wait for the tell-all memoir from someone on the commission before we know for certain, but this is, to my eyes, the result of starting with an agenda. If you’re looking for papers that support an existing position, perhaps a position that was dictated to you by political interests, it makes sense why someone might use citations of unrelated papers, or papers which don’t actually support your position.

If you can’t find any papers that even obliquely support your position? Ask AI for them. After all, ChatGPT doesn’t say no.

(It just hallucinates, instead.)

For anyone reading this, don’t let a dense-looking citation fool you into accepting questionable “facts.” It’s easy to check; just paste the full article title into a search box and check whether the details (author names, journal name, full title) all match up.

Everyone writes with an agenda, and citation managers can make mistakes. The commission has put out an updated report and removed the hallucinations, although there are new issues with misinterpretations of the data, according to some of the original study authors.

Many researchers have praised sections of the report for some of its aspects. Its focus on hyper-processed foods and environmental chemicals are important. But false, shoddy science in some sections undermines the rest of the report.

The next time someone makes a claim, don’t take it at face value — even if it has a citation!